Earth Day and the Industrial Revolution in 3 Graphs

It's Earth

Day. Or it was three days ago. But what we write is still relevant to the

season. In any event, why would we begin

with a picture of world population growth?

Well, the number of people on Earth should have an obvious connection to

Earth Day. But the key to the immediate connection

we want to highlight is the blue line in the graph showing the beginning of the

Industrial Revolution. A neighbor of

mine, a gentleman who's fairly in-the-know about economic issues, stopped me on

the street the other day to ask if I understood how much difference the

Industrial Revolution made to the world's population. He had just learned this, he explained, in an

online course he had taken, and he was stunned.

So I figure if Steve is stunned, maybe some of you are too. So here's some of the story and why we pay

particular attention on Earth Day. It's

not just the numbers of people, but their standards of living that matter.

The key is

the bend in line. The world's

population was basically flat from the year 1 A.D. to 500 A.D. at about 200

million people; estimates show that by 1000 A.D., it was still no more than

250-300 million. Population reached

about 500 million by 1500 and 1 billion in 1800. Now, just 215 years later, there are about

7.2 billion people. The addition of the

last half of that, 3.6 billion, has taken only 45 years. So clearly some very dramatic things happened

around and after 1800.

We often

think of the Industrial Revolution in terms of the cotton gin and other

machinery, but advances in health care and public facilities are also

important. As examples, Edward Jenner's

small pox vaccine came in 1798. John

Wilkinson, an Englishman, developed the iron pipe that made a new water supply

system in Paris in 1786. John Snow realized in 1854 that contaminated

water could contribute to the spread of cholera. Before this period, life expectancy at birth

hovered around 24 years in the medieval period and got to 35 in England by the

mid-18th Century. By 1900, it

reached the late-40s and was about 80 years in 2010. In other words, death rates declined

markedly. This is so all over the world.

At the same

time, birth rates have also declined.

This latter factor has been pronounced enough that population growth

rates have actually moderated in recent decades. Big as the numbers are, they are no longer

accelerating.

Robert

Lucas, a consulting economist to the Minneapolis Federal Reserve Bank, has

written about these birth and death rate trends. As the Industrial Revolution took place,

along with accompanying gains in agricultural output and the improvements to

health, population did expand dramatically.

The gains in production supported the population growth. Thomas Malthus and other economists of his

day – around 1800 – began to fear that this population growth trend would

consume much of the earth's resources, leading to increased poverty. While there is quite justified concern over

that eventuality, Lucas offers some mitigating notions.

At the

outset of the industrial and agricultural revolutions during the 18th

Century, most of society was agricultural, and as farmers obtained larger

yields for their crops and had healthier animals, they used their increased

income to enlarge their families, so they could produce bigger crops still. Living standards – income per person – thus

didn't change much at first. From 1700

to 1820, world GDP firmed from 0.2% growth per year to about 0.5%. But population had almost the same movement,

so each person was associated with about $665 worth of output in 1820, only mildly

larger than the $596 in 1600.

But starting

around 1820, that relationship shifted.

Those health improvements we mentioned before, clean water and similar improvements

to sewage disposal, made conditions much better in cities and people began

moving to them and doing more industrial work.

This coincided with diminishing birth rates, enough so that total production

gains were associated with more production per person; by 1900, that had nearly

doubled to $1,260. By 2008, the latest

year for which we have this specific calculation, world output per person was

just over $7,600, as seen here.

We're

writing about all this because it's Earth Day.

What is the connection? As the

line in the above graph was moving definitively higher in the early 1960s, a

marine biologist named Rachel Carson published Silent Spring, a book that grabbed everyone's attention about how

more people were using more of the earth's resources, much of that in an

ironically unhealthy way. For the first

time, many people came to understand that they could not just plow ahead

unconcerned about what they were doing to the earth and its environment. Would this new realization slow growth?

It took some

time, but progress in making the right use of the earth is taking place. Robert Lucas, in the material we reference

here, counters some environmental naysayers' arguments by highlighting the role

of technology. He points out that we

should use a theory of economic growth that embodies not just numbers of people

and amounts of consumption, but the application of technology, ingenuity and

adaptability.

This notion

prompted us to check out the amount of energy used in producing today's GDP compared

to some historical period. If GDP growth

just uses more and more energy resources, then the naysayers will be right;

succeeding generations of people will indeed be less well off because pure air,

clean water and all kinds of material resources will be scarcer for everyone.

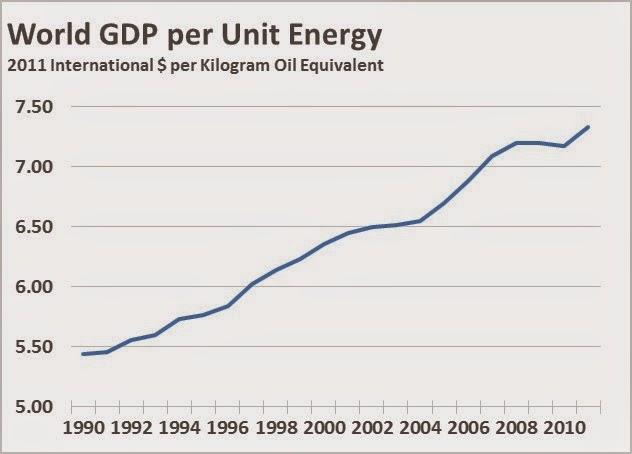

What we

found with some brief searching, is just 20 years' worth of information on

this. But it tells a positive, hopeful

story. Data from the World Bank show

that a fixed unit of energy would yield $5.40 of world GDP in 1990. By 2010, the same amount of energy made $7.20

of GDP.

Further, in

1990, each dollar of GDP was associated with 0.5 kilogram of carbon emissions,

but in 2010, this had fallen to 0.4 kilogram.

Energy use per person has increased for the world as a whole, but this

is happening in middle income regions in Asia, the Middle East and northern

Africa, not in high income regions. In

fact, in many places per capita energy use has gone down; in the U.S., for

example, each person used 7,700 kilograms of energy in 1990, but just over

7,000 kilograms in 2011.

So perhaps Lucas

is correct. If we know and understand a

situation, we can quite probably find ways to deal with it. Thus, growth can continue to the extent that

we become more efficient in using energy, and we can even develop new energy

sources and/or improve the way we manage current sources. We can further reduce pollution without

severely restricting our general ways of life.

This isn't automatic, and we have to be mindful and deliberate in our

efforts, but we have a good shot at continuing to improve our lives and the

life of the Earth itself.

--------------------------------

Sources:

Robert

Lucas. "The Industrial Revolution:

Past and Future." Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, Annual Report

Essay, 2003 Annual Report, published May 1, 2004. https://www.minneapolisfed.org/publications/annual-reports/the-industrial-revolution-past-and-future. Accessed April 24, 2015.

Eric

McLamb. "The Ecological Impact of

the Industrial Revolution". Ecology

Global Network. September 18, 2011. http://www.ecology.com/2011/09/18/ecological-impact-industrial-revolution. Accessed April 24, 2015. Also see McLamb's Earth Day commentary from

2014: "Earth Day and the Human Revolution" http://www.ecology.com/2014/04/22/earth-day-human-revolution/. Accessed April 24, 2015.

Long-term

historical data on population and world GDP are based on Angus Maddison, The

World Economy: A Millennial Perspective.

Paris, France: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. 2001 and 2006. http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/development/the-world-economy_9789264022621-en. A pdf may be purchased or the book may be

read in an e-book format on that site.

Barnes & Noble and Amazon also have it available.

Maddison was

professor at the University of Groningen from 1978 to 1997 and a founder of the

Groningen Growth and Development Centre. He passed away in 2010. His data are recognized as the primary

compilation of long-term world-wide GDP and other economic and demographic

indicators; they are now maintained and made available in spreadsheets on a

site managed by his colleagues at that research center http://www.ggdc.net/maddison/oriindex.htm.

Data on the

relationship of energy to GDP, energy use per person and carbon emissions come

from the World Bank's World Development Indicators. The 2015 edition of these was published just

on April 14, 2015, and includes these energy data through 2011. See http://wdi.worldbank.org/table/3.6

"Energy production and use" and http://wdi.worldbank.org/table/3.8

"Energy dependency, efficiency and carbon dioxide emissions". Accessed April 24, 2015.

Labels: Economy, Environment, Science and Evolution, World